One of the prevailing themes of the modern age is that it represents a grand emancipation from the world religious past and toward a world of science and facts and materialist realism. People are, unless they have been held back by superstitious residues of darkened times, generally enlightened and disposed to the reality discoverable by the scientific method.

There are many ways to challenge this general thesis, but there’s one facet of it that has been called into question by the Romanian professor Ioan Couliano. This facet has to do with the organization and propagation of the myths that drive mass society. As anyone who has looked into Elite Theory— such as described by figures on the Right such as James Burnham and Sam Francis—knows, the formulation of myths is a fundamental prerequisite to organizing the consent of the masses. There are natural or organic myths, as identified by the Old Conservatism of the Western traditionalists (Roger Scruton, Edmund Burke, etc), and there are artificial myths, such as manufactured by the Western Elite of the present age, especially since the Progressive and Managerial Revolutions of the 1910s and 30s. And then with new themes in the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s.

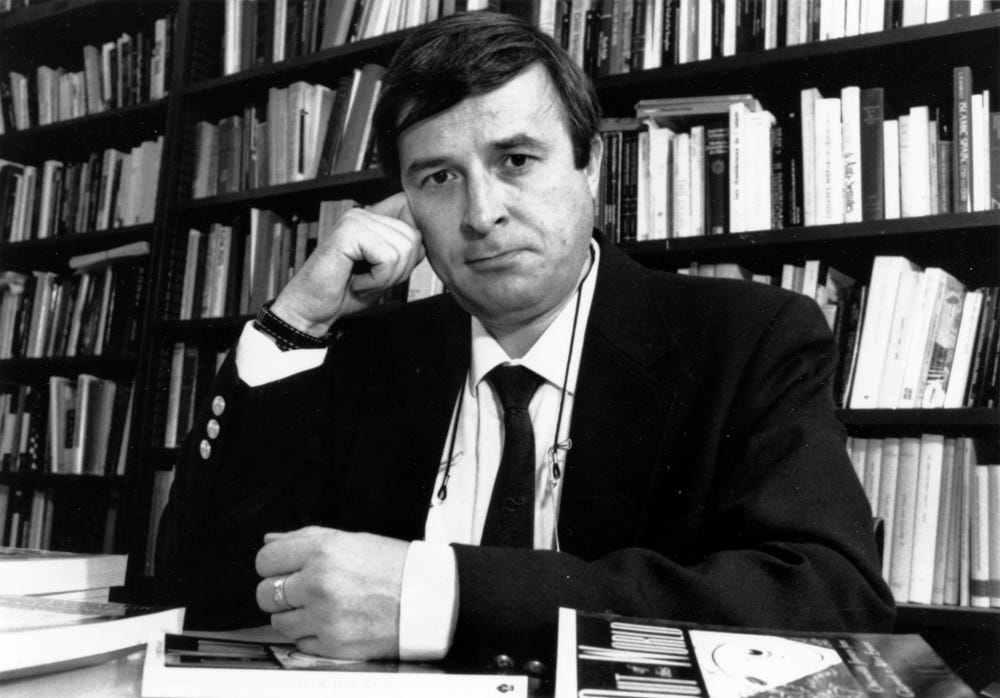

Professor Couliano is himself an interesting figure in the history of the European Right, having at one point been a disciple of the great and legendary Mircea Eliade. Eliade, a historian of world religions, was also a member and sympathizer of various extreme anti-communist movements in the early twentieth century, such as Codreanu’s Iron Guard. One of the motivating aspects of Eliade and Couliano’s work was their realization that if Communism was an artificial manufacturing of the new political order, twentieth century Western Liberal Democracy was not, at its root, any more organic. It too was foisted on its peoples.

There is an interesting discussion in Couliano’s book Eros and Magic in the Renaissance where he explores the 16th century study of magic by the Italian Giordano Bruno. In exploring Bruno’s contributions, Couliano finds application of Bruno’s themes to today’s socio-political order. In finding similarities today with the objectives of magic in the Middle Ages, Couliano controversially concludes that magic as a mechanism of absorbing the attention of masses is a key feature of our age; we have not evolved beyond it.

He notes that “it is still commonly thought that a chasm separates our contemporary view of the world and ourselves from the concepts help by Renaissance man. The manifest sign of this cleavage is supposed to be modern technology….”

And yet, while prejudiced “specialists” scornfully describe the phenomenon of Middle Age magic as primitive and unscientific, Couliano emphasizes the fact that while the means are (apparently) different (science instead of occultism), the ends of scientific technology are similar to those sought in ancient magic: “to produce light, to move instantaneously from one point in space to another, to communicate with faraway regions of space, to fly through the air, and to have an infallible memory at one’s disposal.” All of these (not to mention digital entertainment technology) seek to impress and absorb the attention of the masses, to fill them with awe and inspiration and motivation to live in certain ways.

But more specific to this present post, Couliano seeks to make the case that the driving disciplines that manage our present western world order, such as the “psychological and sociological sciences” have been derived from the themes of Renaissance magic. Bruno holds that the primary objective and animating core of the magician’s function in society is to gain “control over the individual. and the masses based on deep knowledge of personal and collective erotic impulses. We can observe in it not only the distant ancestor of psycho-analysis but also, first and foremost, that of applied psychosociology and mass psychology.”

It is beyond the scope of this post to elaborate on the presence of the erotic in the previous paragraph, and in the title of Couliano’s book. Though one can certainly suspect a connection between the manipulation of the masses and the drastic emphasis on sexual themes in the present moment throughout the media at large (many don’t realize that online conservatives participate in this drive, as they share and comment and making trend the worst of sexual degeneracy).

Couliano is worth quoting at length here:

Insofar as science and the manipulation of phantasms are concerned, magic is primarily directed at the human imagination, in which is attempts to create lasting impressions.

That is, the objective is to impress on the subjects with images and themes that shape and mold the mind and, subsequently, the behavior. The panorama of man’s imaginative world is malleable and the function of the magician, in all epochs past and present, is to structure it in a specific direction.

The magician of the Renaissance is both psychoanalyst and prophet as well as the precursor of modern professions such as director of public relations, propagandist, spy, politician, censor, director of mass communication media, and publicity agent.

Experts in advertising, crafters of brand stories, newscasters, social media managers, entertainment producers. All these, more than in any other age, have access to the masses and must pursue the same objectives and serve the same social function, as the magicians. Couliano is emphatic that “historians have been wrong in concluding that magic disappeared with the advent of ‘quantitative science’” as he argues that the functions of the magician have “simply been camouflaged in sober and legal guises.”

The magician of the modern age “busies himself with public relations, market research, sociological surveys, publicity, information, counterreformation and misinformation, espionage, and even cryptography.”

And as was true of the magician and the enigma of the political power of magic, the objective has remained: to create “a homogeneous society, ideological healthy and governable.” There arises the phenomenon of the Total Manipulator, “who takes upon himself the task of dispensing to subjects a suitable education and religion.” Extreme care, reflects Bruno, must be taken to ensure that the masses are exposed to the right cult, the right books, the right writers, the right narratives of the world. The masses must be supervised so as to be made constantly ideologically fertile and able to be governed.

The world is not the product of man, but man the product of his world.

The masses are supervised, not merely by the state—the social apparatus of coercion—but by a broad swath of social institutions. The classical liberal or libertarian emphasis on the state as the enemy of liberty becomes contorted when it cannot see the systemic enemies that exist outside the apparatus of pure coercion. Here, Couliano, writing in the 1980s, comments that what separates the Communist world from the Western one is that the Communist state was a Police State: it organized and ordered upon pure threats of coercion and violence. Repressing all liberties and hope of liberties, it transformed society into a prison, complete with guards and explicit regularity of mind and body. There is no subtlety, here evil wears no mask. It was a masculine sort of totalitarianism.

The Western State in the social order of post-Managerialism had achieved a triumphant status of a true Magician State, where our world is doused in subtlety, in phantom amusements, constant stimulation toward awe and wonder. Indeed, with the the use of technology (especially digital technology—but Couliano’s writings preceded even the internet), there’s been a democratization of the western participation in the magical, in the ability and desire to manipulate the world and those who make up society. But in involving ourselves in this Magician State, often by means of the so-called market economy, Couliano wonders, are we ourselves the magicians or are we rather sort of sorcerer’s apprentices who are setting “in motion dark and uncontrollable forces?”

He has no committed answer to this question, but predicts that the Magician State would outlast the Police State, not only in the Cold War struggle between East and West, but as a type. The Communist experience failed for a variety of reasons, but related to this analysis, because the magicians our time have rightly surmised that the masses respond better to pleasure than to pain. Making the subjects happy is a contribution of the psychologists, the pharmaceutical companies, the creators of entertainment and luxurious living. All these things, and many more, reinforce the power of the magician state as before our eyes miracles are performed. Acts of wonder are catered to us, breaking us free from the limitations of older epochs, and right into a new form of submission that we have been manufactured to long for.

The ends sought by the magicians of old have not changed, but in the world of science and materialism, their crafts are merely explained in new ways.