Happy William Bradford Day!

It is day eleven of Heritage History month and today we are focusing on one of the greatest of the Puritan settlers. This is another one of those choices where we need to remind people that the point of this isn’t to select a group of individuals with whom we totally agree or who represent the better side of historical divisions, but who had a particular impact on our way of life, especially writing as a Heritage American.

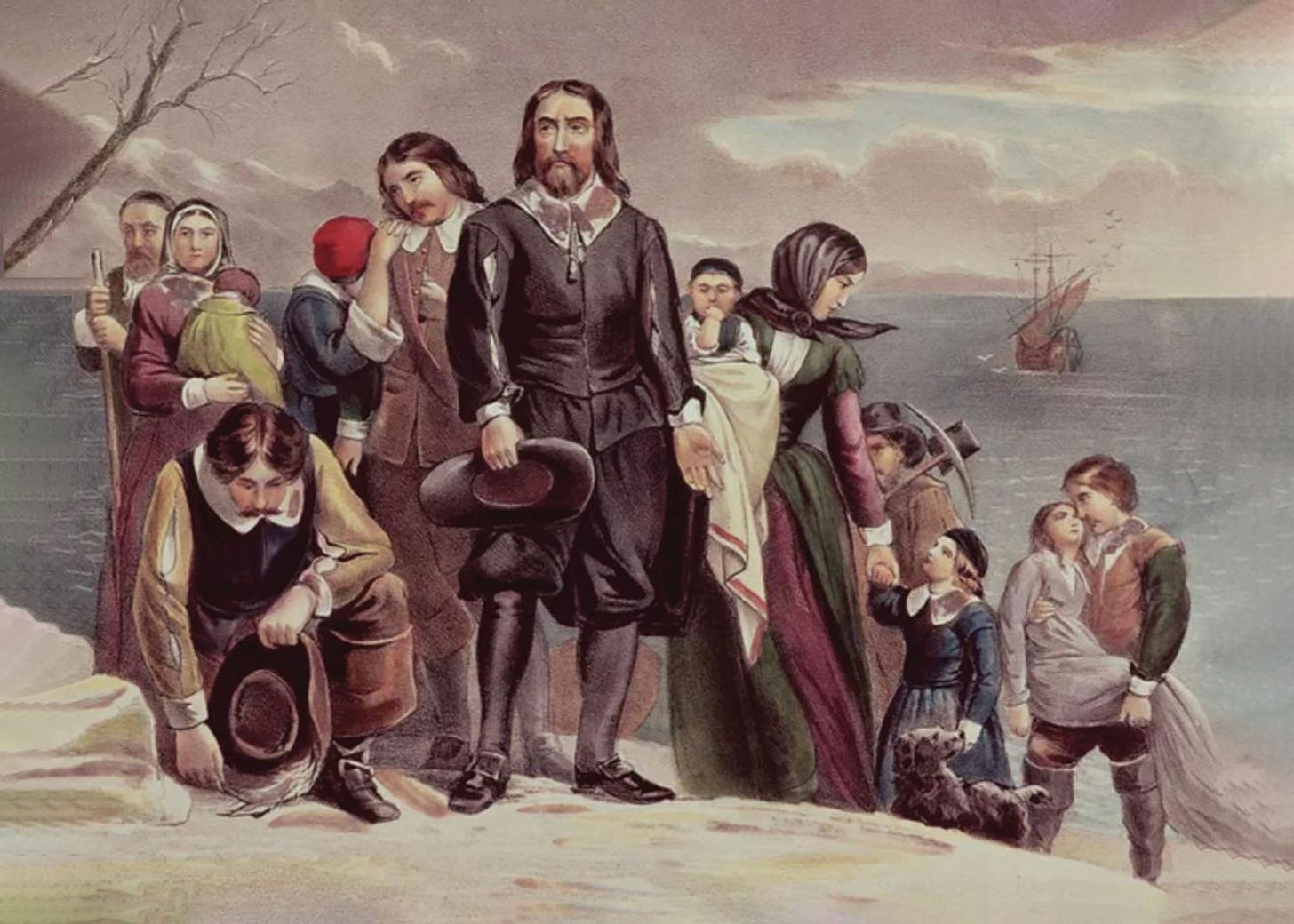

William Bradford of course was among the separatist Pilgrims who determined to leave England, move to the Netherlands, and eventually to the New World, landing up North in Plymouth Bay—this, despite the fact that their original destination was Virginia. Interestedly for those of us who recognize how urgent it is for us to protect our heritage and customs and legacy culture in our time of constant upheaval, the primary motivation for the English pilgrims to leave the Netherlands for the New World was that it was becoming impossible for the English to keep their children from absorbing the Dutch culture of their host country.

This speaks to three things: The Dutch demanded cultural assimilation, the English cherished their culture enough to refuse, but respected the hosts enough to not push for some sort of counter-culture war. We should remember this.

Bradford was a young man when he boarded the Mayflower and had no leadership role. He did volunteer for various exploration parties to choose a site for the settlement. The world that he found in North America was full of danger—both natural and human. On one exploratory outing, he fell into a trap laid by natives. That winter of 1620-1621 saw the Pilgrims in a devastating sickness that killed half the settlers—Bradford was among the sick, but managed to survive.

Bradford was part of the negotiations with the Pokanoket Indians, which proved to be an important strategic military alliance to allow for mutual defense against other, more hostile Indian groups. Bradford spent his years on and off as the colony’s governor building up long standing alliances with willing tribes, establishing and developing the political institutions of the colony, and adapting to changing needs of the growing colony. It would prove to be the first permanent Northern European settlement in North America.

It was Bradford whose diaries and journals we are able to read to get much of the detail about the early years of the Plymouth Colony. He has hence been described as both the “forerunner of literature” in America and “the father of American history.” Bradford’s “Of Plymouth Plantation” is still available in physical copies and decently affordable.

Bradford was one of the signers of the Mayflower Compact, that agreement of consent that established the political unity of the settlers and the social order which would be produced. The purpose of their journey, their colony, and the company was expressly “for the Glory of God and advancement of the Christian Faith and Honour of our King and Country.” They saw themselves not as a new people, but as representative of the English way of life and cultural customs, duty-bound to honor both their natural king and their God.

One of my favorite Bradford lines refers to their realization that private property is the foundation of a functioning social order:

“The failure of this experiment of communal service, which was tried for several years, and by good and honest men proves the emptiness of the theory... applauded by some of later times, — that the taking away of private property, and the possession of it in community, by a commonwealth, would make a state happy and flourishing; as if they were wiser than God.”

One of my favorite settling forebearers