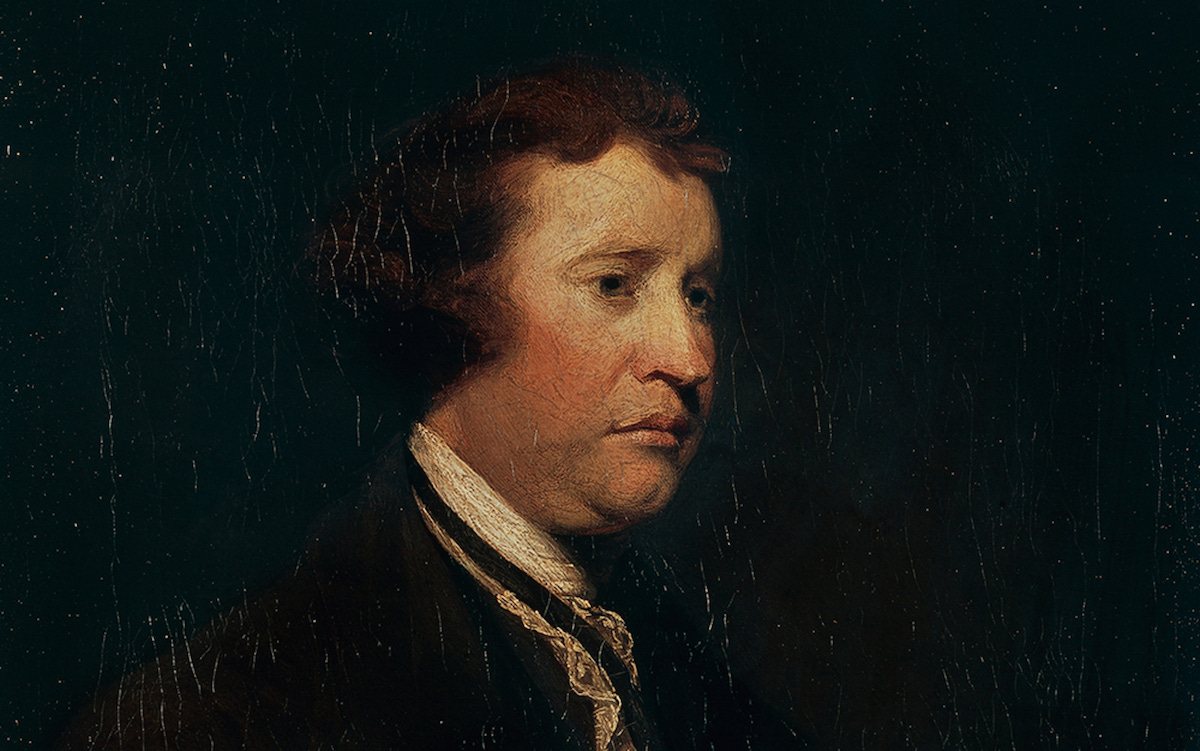

Happy Edmund Burke Day!

It is Day Twenty-Four of Heritage History Month and we are going to look today to the great critic of the French Revolution and the coming of the “Empire of Light and Reason” that would characterize rationalistic modernism. Burke himself cannot be said to embody the full spirit of the Tory traditionalists (he was a Whig), but his understanding of the cataclysmic effects of revolting against the past were profound.

One of the things that I am going to focus on in a coming series of essays is what I call the Sanction of History; history is the vehicle by which Providence manifests our nexus of rights and duties, and this is a major theme of Burke’s Reflections. Man without historical context, without the particularity that shapes him and precedes him, is a dangerous abstract. Burke anticipated the twentieth century’s deracinated mankind; now a cultish belief about individual man that permeates western thinking.

Edmund Burke was intensely opposed to the tendency of political rationalists to reconstruct society in pursuit of claims of justice. While people like Thomas Paine and other agitators of political revolution in America and Western Europe were emphasizing that societies birthed in injustice must be leveled and built anew, Burke would warn that such an attitude toward political affairs would produce the destruction, but never the reconstruction. What history had afforded us, as inheritors of Western Civilization, was a blessing that need to be cherished and protected.

Burke then would have a strong historicist bent that has caused some debate among scholars about his commitment to (a transcendent) natural law vs his implied cynicism about such a concept. I will express my views on this soon enough, but the fact remains that Burke is not of the same genus as those who find political laws as transcending the social order. Alfred Cobban and Francis Canavan have argued well that Burke’s use of Locke’s language, was cultural rather than philosophical.

Burke was of the most moving and stirring writers in the early modern age. And I will end with this profound reflection of the meaning of the French Revolution in what he took to be the close of Western Civilization. Here was an eerie lament at the age to come, the age which we now endure:

But now all is to be changed. All the pleasing illusions, which made power gentle and obedience liberal, which harmonized the different shades of life, and which, by a bland assimilation, incorporated into politics the sentiments which beautify and soften private society, are to be dissolved by this new conquering empire of light and reason.

All the decent drapery of life is to be rudely tom off. All the superadded ideas, furnished from the wardrobe of a moral imagination, which the heart owns, and the understanding ratifies, as necessary to cover the defects of our naked, shivering nature, and to raise it to dignity in our own estimation, are to be exploded as a ridiculous, absurd, and antiquated fashion.